August 26th marks National Dog Day.[i]

The dog is of great importance to the history of medicine. Dogs have played a role for developing new treatments for an array of diseases, most notably diabetes mellitus. In 1889 Joseph von Mering and Oskar Minkowski demonstrated that by removing the pancreas from a dog, the animal developed diabetes: this led to the discovery that insulin regulated sugars in the blood.

The dogs’ significance in the history of research extends into developments of vaccines, toxicity tests and blood transfusions. There is more information on this rather grim history at:

http://www.animalresearch.info/en/designing-research/research-animals/dog/

This article focuses on a slightly happier story, the history of the dog biscuit and the wider context of the retailing of animal products and veterinary medicines within the medical marketplace.

James Spratt launched the dog biscuit in the 1860s in Britain and became a large-scale manufacturer . It was the sight of malnourished dogs surrounding the London docklands that induced him to manufacture biscuits containing beef, wheat, beetroot and vegetables.[ii] As an aside, one of his clerks, Charles Cruft would go on to establish the Crufts championship show for dogs.[iii]

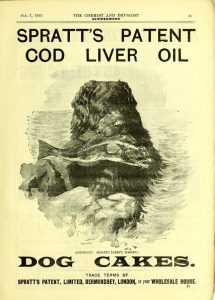

These full-page advertisements from January 7th 1893 in The Chemist and Druggist (courtesy Wellcome library) suggest that Spratt’s dog biscuits and products could be found within the chemist shop at the end of the nineteenth century.

“The manager of Spratt’s patent has sent us a 6d. pamphlet, entitled ” The Common Sense of Dog Doctoring.” The preface explains that it is intended to fill the gap between works too meagre to be of any practical use and others too technical for the general public. It fills 120 pages, and is by no means an advertising puff. The medicines made by the Spratt’s patent are certainly recommended in appropriate places, but they are not the only ones recommended, nor are they pushed forward at every turn. The chapters treat on the following subjects : — Administering medicines, distemper, diseases of the skin, goitre or bronchocele, warts, abscesses, diseases of the respiratory organs, of the bowels, liver, milk glands, urinary organs, generative organs, and of the mouth and teeth ; salivation, diseases of the eye, ear, feet, nails and tail, and of the nervous system, rheumatism, rabies, poisons, worms, vermin, rickets, accidents, breeding, and rearing. It will be seen that the field is extensive, but each subject is treated instructively, with an evident acquaintance with recent advances. Every one of our readers would do well to secure a copy.”[iv]

Competition was rife for the retail chemist at the turn of the century. In order to compete with each other many pharmacies offered long opening hours or specialised services such as photographic, dental, optical or veterinary services. No special authorisation was required for these ad hoc activities, . Veterinary practice became an important part of British retail pharmacy in the period, although due to the limited therapeutic value of the veterinary medicine, many animals tended to be slaughtered rather than treated. This was also the same for small domesticated pets and many chemists offered a euthanasia service at the back of the shop for untreatable illnesses.[v] An array of animal products and services could be found in ordinary chemists shops at the turn of the century.[vi] Sheep dip was another was another veterinary product found advertised in The Chemist and Druggist.

courtesy Wellcome library

In 1900, the population of Britain’s animals matched that of humans. Horses in particular were of significance to British society before mechanized traction and transport, and horse powders and horse balls were routinely made up at chemists or bought in from wholesalers like Allen & Hanbury. These contained aloes to create a laxative effect.

Advertisement for horse remedies from The Chemist and Druggist, 25th June 1910, p. 3 (courtesy Wellcome library)

During this period, human and animal diseases were treated in a similar manner. For example, in both humans and animals, laxatives were widely used in an attempt to cleanse the digestive system and restore balance. Pharmaceutical development of drugs specifically for animals did not begin properly until the 1950s and the advent of sulpha drugs. In the early part of the 20th century medicines for animals and people were interchangeable . Veterinary products were usually just lower-cost human variants.

Courtesy Wellcome library

A flick through advertisements found in copies of The Chemist and Druggist will highlight the importance of veterinary practices and animal products for the retail chemist in the period. Go to the Wellcome Library’s website to access the online resource: http://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b19974760

Blog post by BSHM Social Media Editor Laura Mainwaring

[i] http://www.nationaldogday.com/]

[ii] http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/evancoll/a/014eva000000000u06201000.html

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Cruft_(showman)

[iv] The Chemist and Druggist, 15th April 1884, p. 182

[v] S. Anderson, Horse balls and lethal chambers: the veterinary chemist in Great Britain 1900 to 1948. Pharmaceutical historian, 33: 2 (2003). pp. 29-32

[vi] T.A.B Corley and Godley, A, ‘The veterinary medicine industry in Britain in the twentieth century’ The Economic History Review, 64, 3 (2011), pp. 833- 836