Polio is highly culturally evocative – vaccines on sugar lumps, children in callipers and lifetimes in iron-lung respirators. The Bulletin, published by The British Polio Fellowship, provides an additional perspective. It gives an insight into how polio-disabled people understood and wished to represent themselves. Charlotte Stobart explains.

In 1939, Patricia Carey, who contracted polio in India as a child, and Frederic Morena, a stage actor who contracted polio at 42 and was subsequently wheelchair bound, founded the Infantile Paralysis Fellowship as an advocacy and self-help society.

This organisation, which became the British Polio Fellowship, initially attempted to address both the physical and social limitations of polio-disability, focusing on mutual support and personal development. From its inception, the Fellowship published a bimonthly newsletter for members.

The first major British polio epidemic came in 1947, and outbreaks of polio (nicknamed the ‘summer scourge’) occurred regularly until the 1956 advent of the Salk Vaccine. The number of cases came down, but the disease left many people with lifelong disabilities. Many developed post-polio syndrome, sometimes as much as 40 years after the original infection.

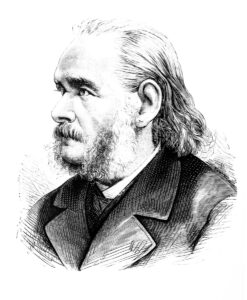

A regional water polo team. Young men with characteristic polio-disability. The Bulletin, May 1969, p. 8, The British Polio Fellowship Archive

By 1965, the fellowship had around 12,000 members to whom it circulated the newsletter, called the Bulletin. This was a bottom-up, collective project, and the polio-disabled readership provided the bulk of copy and photographs (including of sports days, holidays and weddings). Similarly, patients at the Spinal Injuries Unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire, wrote and edited their own community building publication, The Cord, from 1947.

Active and positive

The Bulletin consciously and consistently portrayed polio-disabled people enjoying a range of experiences, triumphing over polio and over societal assumptions about the limitations of disabled people. It challenged dominant sociocultural narratives of loss and trauma, and provided polio-disabled people with representational agency and a positive sense of identity and community.

The iconic ‘Action for the Crippled Child’ charity collection boxes of the 1960s showed a young boy with his crutches and callipers. He is despondent, evoking charitable pity (and hopefully, donations). Conversely, editions of The Bulletin from the 1960s used pictures of a group of young men on crutches playing football, a team of water polo players with characteristic signs of polio paralysis in their asymmetric legs and a man in a wheelchair being lifted (somewhat inexplicably) by crane onto a ship.

Through the 1960s, understandings of polio shifted as the public health threat waned. As their numbers and cultural purchase naturally decreased, polio-disabled people were increasingly overlooked by mass-media, and polio itself became increasingly regarded as a phenomenon of the past or other global regions.

Thanks in no small part to the work of the British Polio Fellowship and The Bulletin, the polio-disabled identity developed positive connotations: determination, hard-work and tenacity. The Bulletin allowed British polio-disabled people to continue to assert their presence and identity and raise funds for assistive technologies, activities and residential homes for their ageing cohort. The British Polio Fellowship continues to publish The Bulletin to this day, advocating for the 47,000 people in Britian still living with the late effects of polio.

Charlotte Stobart is an MA student of History of Technology, Science, and Medicine at the University of Manchester.

References and further reading

The British Polio Fellowship: https://www.britishpolio.org.uk/

The Bulletin Archive- stored at the British Polio Fellowship Office in CP House, Otterspool Way, Watford WD25 8HR.

Brady, Sam, The Cord, https://www.paralympicheritage.org.uk/blog/the-cord-journal-for-paraplegics, National Paralympic Heritage Trust, 20 July, 2020.

Couser, Thomas, “Disability, Life Narrative, and Representation.” PMLA 120:2 (2005): 602–6

Williams, Gareth, Paralysed with Fear: The Story of Polio. London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013