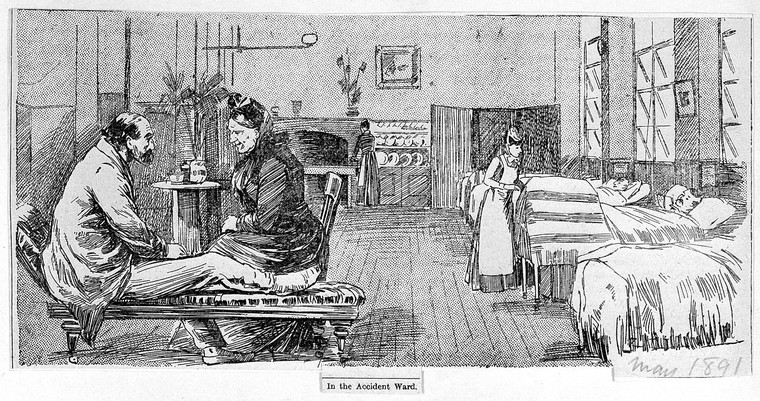

Is the patient a case, a body or a partner with power? Christine Gowing looks at the changing perspective in medical history.

nursingtimes.net

In 1945 the patient voice was merely a distant echo. That year the medical historian Douglas Guthrie published a paper The Patient: a neglected factor in the history of medicine[1], arguing that the patient’s part in the march of medical progress had long been missing while attention had been devoted to the achievements of science and physicians.

The history of medicine was the history of doctors, or, as Roy Porter put it, ‘a history from above and populated with heroes.’[2] It was only in the 1960s and 1970s that historians began to look at how wider sociological contexts – social, cultural, professional and economic frameworks – influenced medicine’s history.[3]

But how culpable are we still as medical historians when we push the patient out of the narrative?

The presence of patients throughout history has often been denied, simply due to lack of information about them – and at what point did patients anyway emerge with any significance or autonomy in the doctor-patient encounter?

The historian Edward Shorter blamed the science of healing in the 1940s and 50s for overwhelming the art of healing[4], extending Foucault’s claim that clinical medicine was responsible for depersonalisation and the sidelining of the patient.[5]

The patient contributes

It was psychoanalyst Michael Balint’s work in the 1950s that first recognised and encouraged the emergence of the patient in the medical consultation.[6] Balint’s psychodynamic analysis and his understanding of the patient’s contribution enhanced the consultation as a therapeutic tool. Increasingly accepted, this approach encouraged the involvement of patients in the management of their condition, although in the 1980s, medical ethicist Jay Katz would still argue that the doctor-patient power relationship was impacting patients’ decision-making.[7]

And nurses’ relationship with patients? It may be a surprise to hear that it was only in 1962 that nursing training formally recognised the importance of this relationship by including an element on the topic for the first time in the training syllabus.[8]

But now we find the patient as a media star. Remember the momentous day of the first Covid-19 vaccination (outside of a trial) on 8 December 2020? What a victory for science and medical research, for the extraordinary work of the laboratory teams in developing the vaccine and giving hope to a pandemic-torn world.

However, the image that we probably recall most vividly on that day – and the one that dominated the media throughout the world – was of the first vaccinated patient, 90-year old Maggie Keenan. On 9 December 2020, the Daily Express exclaimed:

‘ONE SMALL JAB FOR MAGGIE …ONE GIANT LEAP FOR ALL OF US’

On the same day, the Metro showed an image of nurses providing a guard of honour as she left the vaccination clinic. What we remember in the future when recounting the narrative of Covid-19 – along with the triumph of science and physicians – may be the image of Maggie.

A named patient placed at centre stage.

Christine Gowing has an MA in the history of medicine with research on 18th and 19th century electrotherapy. She later gained a PhD in the history of the relationship between complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and biomedicine. The development of the therapeutic alliance in healthcare is a particular interest.

References

[1] Guthrie, D., A History of Medicine(1945).

[2] Porter, R. (ed), Patients and Practitioners (1985).

[6] Balint, M., The Doctor, his Patient and the Illness (1957).

[7] Katz, J., The Silent World of Doctor and Patient (1984).).

[8] National Archives, Kew, London, General Nursing Council papers, confidential minute, Education and Examination Committee (7 September 1960), DT38/155.

[5] Foucault, M., The Birth of the Clinic (1989).

[6] Balint, M., The Doctor, his Patient and the Illness (1957).

[7] Katz, J., The Silent World of Doctor and Patient (1984).).

[8] National Archives, Kew, London, General Nursing Council papers, confidential minute, Education and Examination Committee (7 September 1960), DT38/155.

[4] Shorter, E., Bedside Manners: the troubled history of doctors and patients (1985).

[5] Foucault, M., The Birth of the Clinic (1989).

[6] Balint, M., The Doctor, his Patient and the Illness (1957).

[7] Katz, J., The Silent World of Doctor and Patient (1984).).

[8] National Archives, Kew, London, General Nursing Council papers, confidential minute, Education and Examination Committee (7 September 1960), DT38/155.

[3] Waddington, K., An Introduction to the Social History of Medicine: Europe since 1500 (2011).

[4] Shorter, E., Bedside Manners: the troubled history of doctors and patients (1985).

[5] Foucault, M., The Birth of the Clinic (1989).

[6] Balint, M., The Doctor, his Patient and the Illness (1957).

[7] Katz, J., The Silent World of Doctor and Patient (1984).).

[8] National Archives, Kew, London, General Nursing Council papers, confidential minute, Education and Examination Committee (7 September 1960), DT38/155.