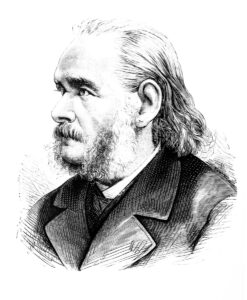

Standing on the deck of the exploring vessel Pleiad in July 1854, Edinburgh trained doctor William Balfour Baikie was about to lead an expedition into the interior of Africa to test the validity of a cure for malaria, writes Wendell McConnaha.

Baikie had been seconded to the mission sponsored by the merchant Macgregor Laird and the Royal Geographical Society, which would leave from Fernando Po, an island in Equatorial Guinea, now called Bioko. Baikie was initially to serve as naturalist and assistant surgeon, but a series of events had elevated him to the expedition’s leader.

For years, men had attempted to explore the path of this great river and, although they encountered natural barriers and local hostility, it was malaria that threatened to cut short the life of any European who ventured inland, and the Bight of Benin was referred to as the Whiteman’s Grave. As the anonymous rhyme said: “Beware and take care of the Bight of Benin. There’s one comes out for forty goes in.”

Although the death rate among Europeans traveling into the interior in this part of Africa often exceeded 70 percent, the focus up to the time of Baikie’s voyage was curing the disease rather than looking for a prevention, and even the preferred method for treating those contracting the disease remained in doubt.

As early as 1630, Jesuit Brothers working in Peru had observed the Quechua Indians using bark from the cinchona tree in treating malaria. The bark was collected, dried, ground into a fine powder and mixed with water to form a strong tea. The treatment had quickly been adopted by the crews of slave ships traveling between Europe, Africa and South America. Royal Naval surgeons soon began utilizing the treatment for sailors who had contracted malarial fever. In 1817, two French chemists isolated the crystals within the bark naming their extract quinine. However, bloodletting and purgatives remained the standard methods of treating malaria within the general medical establishment.

Not just treating

In 1847 Dr Alexander Bryson, an Assistant Surgeon in the West Africa Squadron, presented the Admiralty with a report in which he announced the use of quinine had cut the mortality rate in half, and proposed quinine might also be used as a prophylactic. Baikie was convinced that Bryson was correct in his assumption. Although the purpose of his mission was to explore the Niger and Benue rivers and establish trading sites, Baikie would also use his command position to conduct the first clinical trial testing Bryson’s theory.

Each crew member would be given two-thirds of a glass of wine containing five grains of quinine each morning and a second glass before retiring in the evening. Baikie was staking his reputation and the lives of those under his command on this untested theory. If he were correct, the centre of Africa would be opened to outside exploration. If wrong, he could lose his life and the lives of all those entrusted to him.

On 7 November the Pleiad returned to Fernando Po. They had been on the river for 118 days, explored and charted over 600 miles, and established a series of trading sites. Most importantly, for the first time in the history of African exploration, they had completed the mission without the loss of a single life.

Baikie travelled to England, published the journal of his exploring voyage and then returned to the Niger, where he spent his last five years living alone among the Igbo. His enlightened approach in working with the indigenous people earned him such respect that to this day the Igbo word for “white man” is “Beke.” Baikie died at age 39 of tropical fever. Revered in Africa, his role in establishing a prevention for malaria is largely forgotten by the rest of the world.

St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, Orkney Library and Archives

Professor Wendell McConnaha is a retired university professor in education who has worked around the world. When in Nigeria, he first learned of William Baikie and resolved to write his story, which he has now done in The King of Lokoja: William Balfour Baikie the Forgotten Man of Africa.

References and further reading

Christopher Lloyd, The Search for the Niger, (London, Collins, 1973), pp. 21-22

C. M. Posser and G. W. Bruyn, An illustrated history of malaria, (New York, NY:

Alexander Bryson, Report on the Climate and Principal Diseases of the African Station, Printed by order of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, (London, W. Clowes and Sons, 1847)