“Gentlemen – I have the honour to wish you a scientific Christmas and a drug-devouring New Year”

– Fred Reynolds, co-founder of the British Pharmaceutical Conference[i]

The concept of Christmas adverts feels very twenty-first century, particularly with the rise of emotionally intense adverts that use neuroscience to research how to effectively communicate with the consumer’s subconscious. Today it feels the real meaning of Christmas has lost out to excessive consumerist consumption, but the Victorian ‘nation of shopkeepers’ also used Christmas for commercial gain. The rise of consumer capitalism has been addressed by Brewer and Porter with the identification, from the 1850s onwards, of the growth of advertising, department stores, international exhibitions, consumer psychology and industrial design.[ii] There was a marked transformation in shopping in the Victorian era and it is possible to identify modern advertising techniques.

This wider marketplace is of great significance to the medical marketplace, particularly as the emergence of the chemist and druggist was part of the commercialisation of society. The world of medicine was a commercial venture and there is evidence found in the trade periodical The Chemist and Druggist that the pharmaceutical trade started to utilise the Christmas season for their own commercial gains. It was reported in the periodical by a critic that “Christmas always gives the chemist an opportunity to disguise the real nature of his mission, and bring himself in line with the festive spirit of the occasion.”[iii]

The late 1880s seemed to be a turning point for appropriating the Christmas season for commercial gains – with more references in The Chemist and Druggist to ‘Christmas prices,’ ‘Christmas Decoration,’ and ‘Suitable Christmas Presents.’ As ever, Burroughs Wellcome & Co were at the forefront of marketing, and promoted their products at “special Christmas prices,” or specifically as Christmas presents.

Figure 1 – Burroughs, Wellcome & Co Christmas advertisement[iv]

In the late 1880s Burroughs, Wellcome & Co produced a Medical Pocket Diary, which formed ‘a very suitable Christmas card for chemists to send to their medical patrons.’[v] Their ‘ABC Medical Diary’ was similarly marketed as a gift for the medical profession.[vi]

Fig 2 Burroughs, Wellcome ABC Medical Diary advertisement [vi]

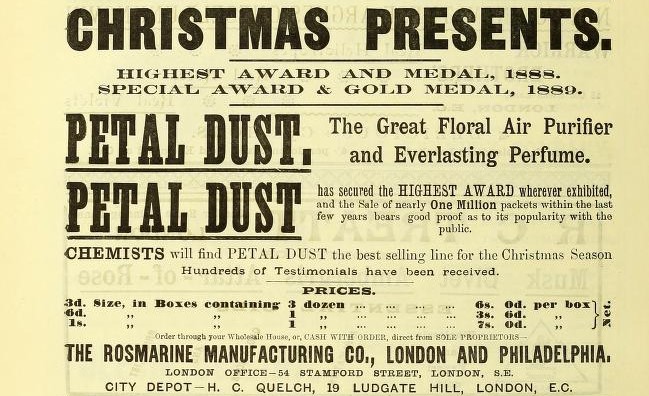

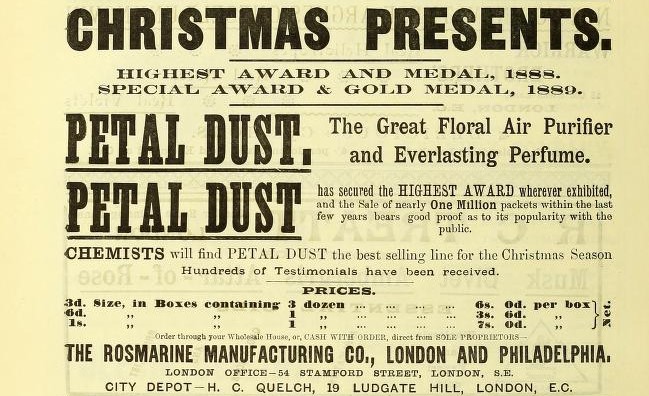

The Christmas novelty can be found in the periodicals’ advertisements throughout the late nineteenth century but predominately for toiletries, perfume, or ‘scientific’ devices. Below are some adverts placed by manufacturers making explicit reference to the festive season as a means to promote their products to the retail trade:

Figure 3 – Perfumes were popular products sold in chemists’ shops.

“Chemists will find PETAL DUST the best selling line for the Christmas Season”

Figure 4 – A Beecham’s advert that includes a New Year’s puzzle and festive poem[vii]

Figure 5 – Blondeau et Cie used Christmas to promote their Vinolia products.

Retail chemists’ shops were encouraged to buy a specific amount in order to receive a “Christmas Gift” [viii]

Taking advantage of the Christmas season was not just a commercial opportunity for large manufacturing chemists. Smaller local chemists were also able to cash in.The Chemist and Druggist reported in December of 1896[ix] that:

“At this season of the year chemists are not behind their neighbours in attracting customers”:-

And listed a whole range of chemists marketing ploys:

Mr Herbert W. Seely, Southgate, Halifax, is presenting his customers with a pretty thermometer.

Mr F.G.da Faye, chemist and mineral-water maker David Place, Jersey, is distributing letter-racks gratis to his customers and giving one to every applicant.

The “Christmas Welcome” presented by Messrs. Fukker & Co., chemists, Norwich, is an original conception containing poetry, tales, conundrums, and other seasonable reading, interspersed with advertisements. It is a good idea well carried out.

Messrs. F.H Prosser & Co, pharmaceutical chemists Spring Hill, Birmingham, publish an almanac and price-list which extends to 184 pages plus insets. There are notes on domestic medicine, and, most wonderful of all, advertisements of a dozen local chemists.

Mr. J. L. P. Hollingworth, chemist and druggist, 21 New Street, Barnsley, and Cudworth, announces that to every person spending Is. and upwards at his establishment he will present a sixpenny Christmas Annual.

The Edme Malt extract Company (Limited), Mistley, wish the trade a very happy Christmas and prosperous New Year on a reply post- card — which to us is a new idea.

The Victorian era was also a time when shop windows and display cases became sophisticated advertising spaces to attract custom.

![L0030356 A grocer's shop in England: doorway and shop window. Photogr Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org A grocer's shop in England: doorway and shop window. Photograph. Photograph 1900 Published: [ca. 1900?] Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/](https://bshm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/shop1900-1.jpg)

Figure 6 – A shop window, 1900 – Credit: Wellcome Library, London

The Chemist and Druggist evidently realised the importance of this phenomenon for the trade and published advice on how to create an attractive Christmas window.

“In the space between the stands and the window arrange neat boxes of perfumes, or anything suitable for presents; then bang from the top ” falling snow,” which may be made by small tufts of cotton wool attached deftly to fine white cotton, and woven together irregularly; … The side stands to be arranged with proprietary articles suitable for the season, as cough mixtures, etc. ….At the back of and over the doors scarlet chest-protectors might be fixed evenly, on which might be worked by pearl- coated pills, string together appropriately, “A Jolly Xmas!” [x]

Their advice seemed well received, a commentator on chemists’ shops in Dublin, Ireland remarked,

“The windows of a number of pharmacies are very neatly dressed with Christmas goods. I can see many instances where the craft have benefited by your valuable hints; an artistic arrangement taking the place of the odd medley which used to prevail”[xi]

With Christmas over a chemist reflected on the Christmas present-giving craze and looked hopefully towards a consumerist future:

“Before Christmas, we have been advising the trade to stock a certain class of goods suitable for presents, but surely it is a wise thing to have a good display of articles of this kind all the year through. In the matter of perfumes, for example, people are always wanting them. Birthdays come; presents are wanted then. Love is ever with us, and its path is strewn with perfume.”

Articles and advertisements from The Chemist and Druggist show that even in the nineteenth century Christmas was being exploited for commercial ends in the retail Pharmaceutical sphere- perhaps all a precursor to the extensive twenty-first century Boot’s Christmas Catalogue!

Only medical men could prescribe medicines under the 1815 Apothecaries Act- Chemists and Druggists were only allowed to supply these substances. So I will end with some Christmas humour from The Chemist and Druggist’s correspondence advice column, in which a chemist inquires,

“If I should meet with any accident on Christmas Day which should afflict me with headache on the morning of the 26th, may I without infringing the Apothecaries Act mix for myself a “short draught,” or must I apply to a duly qualified medical man?”[xii]

References

[i] The Chemist and Druggist, December 25th 1886, p.841

[ii] See: J. Brewer and R. Porter (1993) Consumption and the World of Goods (Routledge, London and New York) and N. Mckendrick, J. Brewer & J.H Plumb (1982) Birth of a Consumer Society: Commercialization of Eighteenth Century England (London, Europa Publications Limited)

[iii] The Chemist and Druggist, 26th December 1886, p. 913

[iv] The Chemist and Druggist, 22nd December 1888, p. ix

[v] The Chemist and Druggist, 24th December 1887, p.819

[vi] The Chemist and Druggist, 20th December 1890, p. 13

[vii] The Chemist and Druggist, 21st December 1889, p. iii

[viii] The Chemist and Druggist, 13th December 1890, p. 15

[ix] The Chemist and Druggist, 26th December 1896, p. 912

[x] The Chemist and Druggist, 22nd December 1888, p. 847-848

[xi] The Chemist and Druggist, 22nd December 1888, p. 841

[xii] The Chemist and Druggist, 15th December 1896, p. 514

Laura Mainwaring

![L0030356 A grocer's shop in England: doorway and shop window. Photogr Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org A grocer's shop in England: doorway and shop window. Photograph. Photograph 1900 Published: [ca. 1900?] Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/](https://bshm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/shop1900-1.jpg)